In

1860,

New

Jersey

was

evolving

from

a

rural,

parochial

past

into

an

industrial,

cosmopolitan

future.

Immigrants

flowed

into

the

state’s

northeast

through

the

nation’s

greatest

port

of

entry,

New

York,

filling

a

growing

need

for

labor

in

an

expanding

economy,

yet

giving

rise

to

social

and

political

tensions

with

the

established

order.

New

Jerseyans

had

begun

to

address

the

greatest

of

America’s

economic

and

social

dilemmas,

race-based

slavery,

as

early

as

the

eighteenth

century,

when

Quakers

condemned

the

“peculiar

institution”

and

Revolutionary

patriots

perceived

the

inherent

contradiction

between

it

and

their

cause.

Although

there

was

opposition

from

the

state’s

slaveholders,

a

gradual-

abolition

act

passed

in

1804

was

reinforced

by

stronger

legislation

in

1846.

Still,

the

1860

census

for

New

Jersey

listed

eighteen

elderly

slaves,

redesignated

“apprentices

for

life.”

While

a

significant

minority

of

New

Jerseyans

was

somewhat

sympathetic

to

Southern

interpretations

o

f

state

and

property

rights,

there

were

few,

however,

who

believed

in

the

right

of

secession,

or

the

extension

of

slavery

into the territories.

Although

most

of

New

Jersey’s

people

were

content

to

leave

slavery

alone

where

it

already

existed,

there

was

an

active

abolitionist

community

in

the

state

by

the

1850s.

In

the

years

leading

up

to

the

Civil

War,

New

Jersey

boasted

a

significant

number

of

“Underground

Railroad”

stations.

Stretching

from

Cape

May

to

Jersey

City,

these

havens

harbored

slaves

escaping

to

freedom.

Important

“conductors”

included

Harriet

Tubman,

then

a

Cape

May

hotel

cook,

and

William

Still,

New

Jersey

born

administrator

and

chronicler

of

the

“Railroad.”

The

state

also

provided

a

refuge

for

the

Grimke

sisters,

prominent

white

Southern

abolitionists,

and

produced

home-grown

anti-slavery

activists

like

Doctor

John Grimes of Boonton.

In

the

1860

election,

the

ambivalent

majority

of

New

Jersey

voters

split

their

electoral

vote

between

Abraham

Lincoln

and

Stephen

A.

Douglas.

There

was

no

great

enthusiasm

for

war

in

the

state,

but

the

Confederate

attack

on

Fort

Sumter

ignited

a

patriotic

firestorm,

and

New

Jersey

sent

the

first

full

militia

brigade

to

defend

Washington.

By

the

end

of

the

conflict,

the

state

had

raised

thirty-three

regiments

of

infantry,

four

of

militia,

three

of

cavalry

and

five

batteries

of

artillery.

The

New

Jersey

adjutant

general

recorded

88,305

men

who

served

during

the

war,

including

New

Jerseyans

who

fought

in

other

states’

units

and

more

than

2,900

black

Jerseymen

who

served

in

the

United

States

Colored

Troops

and

navy.

More

than

6,200

of

these

men

died

in

service

from

combat

and

non-combat

causes,

including

as

inmates

of

prison

camps.

Twenty-six

soldiers

from

New

Jersey

regiments

were

awarded

the

Medal

of

Honor,

as

were

six

sailors

and

two

Marines

credited

to

New

Jersey

and

several

men

born

in the state but serving from other states.

New

Jersey’s

soldiers

were

a

diverse

lot,

representing

the

ethnic

and

religious

mosaic

that

became

the

state’s

twentieth-century

trademark.

Among

them

were

native-born

Protestant

descendants

of

the

original

Dutch

and

English

settlers,

like

Colonel

Gilliam

Van

Houten

of

the

Twenty-first

New

Jersey

Infantry

and

Surgeon

Gabriel

Grant

of

the

Second

New

Jersey

Infantry,

and

Jews

like

the

capable

Captain

Myer

Asch

of

the

First

New

Jersey

Cavalry.

And

then

there

were

Catholic

Irishmen,

like

Captain

Michael

Gallagher

of

the

Second

New

Jersey

Cavalry,

a

leader

in

the

greatest

POW

escape

in

American

military

history.

There

were

Italians,

like

musician

Alexander

Vandoni

of

the

Twenty-seventh

New

Jersey

Infantry,

Poles,

like

dashing

Colonel

Joseph

Karge

of

the

Second

New

Jersey

Cavalry

and

Germans,

like

Captain

William

Hexamer

of

the

First

New

Jersey

Artillery’s

Battery

A.

Two-thirds

of

the

men

in

the

Fifth

New

Jersey

Infantry’s

Company

C,

recruited

in

Hudson

City

(part

of

today’s

Jersey

City),

including

Mexican

Corporal

Calisto

Castro,

were

foreign

born.

Beginning

in

1863,

New

Jersey’s

African

Americans

flocked

to

the

colors

as

well,

including

Sergeant

William

Robinson

of

the

Twenty-second

United

States

Colored

Infantry,

who

was

commended

by

his

captain

as

“especially

distinguished

for

gallant

conduct,”

and

Sergeant

George

Ashby

of

the

Forty-fifth

US

Colored

Infantry,

who

died in 1946, the last surviving New Jersey Civil War soldier.

New

Jersey’s

women

made

their

presence

known

on

and

off

the

battlefields,

and

included

nurses

like

Cornelia

Hancock,

who

was

known

as

“America’s

Florence

Nightingale,”

and

Somerville

native

Arabella

Wharton

Griffith

Barlow,

who

nursed

her

husband,

a

general,

back

to

health

and

later

died

of

typhus

while

tending

sick

soldiers.

Nationally

known

Trenton

poet

Ellen

C.

Howarth

supported

the

troops

in

writing,

with

works

like

“My

Jersey

Blue,”

and

famed

artist

Lilly

Martin

Spencer

of

Newark

painted

the

story

of

the

home

front,

while

noted

abolitionist

Rebecca

Buffum

Spring

turned

her

Perth

Amboy

Eagleswood

School

into

a

military

academy,

putting

her

natural

pacifism

on

hold

for

the

greater good.

Despite

a

strong

pro-southern

“Copperhead”

element

in

the

state

and

the

fact

that

New

Jersey’s

electoral

vote

went

against

President

Lincoln

in

the

election

of

1864,

governors

Charles

Olden

and

Joel

Parker

strongly

supported

a

Union

victory

and

future

governor

Marcus

Ward

provided

so

much

aid

and

comfort

to

military

men

and

their

families

that

they

dubbed

him

“the

soldier’s

friend."

Abroad,

New

Jersey

diplomats

like

William

L.

Dayton

and

Thomas

H.

Dudley

contributed

materially

to

the

Union

cause

by

blocking

Confederate

attempts to secure foreign assistance.

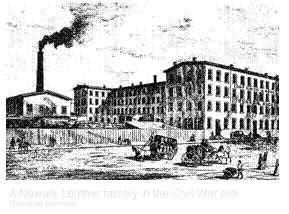

In

1840,

27,000

New

Jerseyans

were

involved

in

industrial

production.

By

1860,

that

number

had

more

than

doubled.

New

Jersey’s

industrial

might

soon

went

to

work

to

help

win

the

war,

as

the

state’s

civilian

manufacturing

base

rapidly

converted

to

military

production

in

a

preview

of

the

nation’s

World

War

II

experience.

Garment

makers

like

John

Boylan

of

Newark

and

Nathan

Barnert

of

Paterson

manufactured

hundreds

of

thousands

of

uniforms,

while

cutlery

manufacturers,

including

James

Emerson

of

Trenton

and

Henry

Sauerbier

of

Newark,

turned

out

thousands

of

swords

and

bayonets.

Skilled

workmen

at

Charles

Hewitt’s

Trenton

Iron

Works

made

1,000

musket

barrels

a

week

at

the

height

of

the

war

and

Paterson’s

Rogers,

Ketchum

and

Grosvenor

Locomotive

Works

built

many

of

the

railroad

engines

that

contributed

to

the

significant

Union

technological

advantage

that

tipped

the

scales

to

victory.

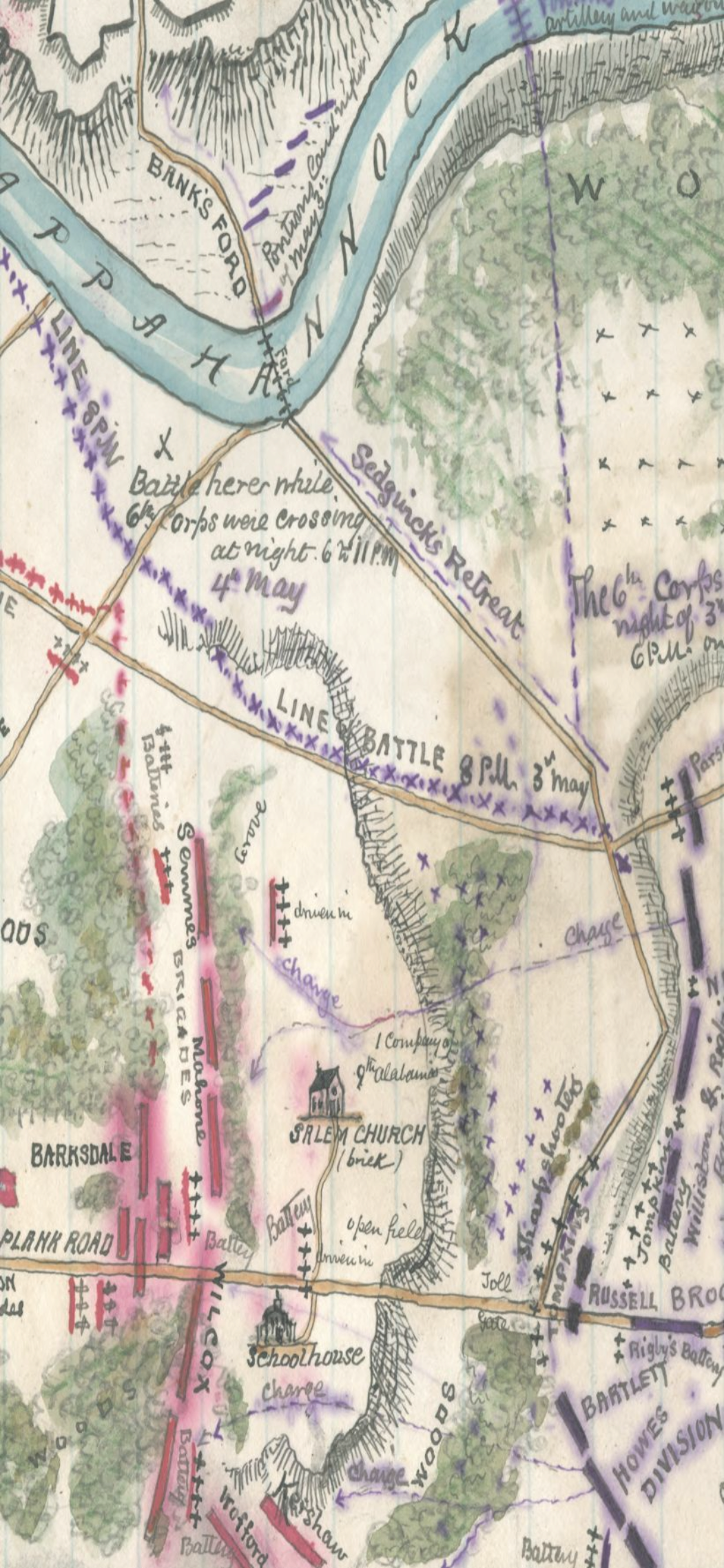

New

Jerseyans

fought

in

all

the

war’s

major

campaigns,

distinguishing

themselves

in

numerous

battles.

The

state’s

citizens

supported

their

soldiers

in

the

field

and

produced

the

sinews

of

war

that

made

victory

possible.

All

of

their

sacrifices

assured

the

survival

of

a

united

and

free

country.

It

was

not

a

country

without

problems,

but

one

with

infinite

possibilities

that

have

carried

us

into

the

twenty-first

century.

For

this

we

owe

a

deep

debt

of

gratitude

to

those

long

dead men and women of the nineteenth century. And for this we will remember them.

- Joseph G. Bilby

New Jersey in the Civil War

Civil War Heritage Assn